by Lara Rössig

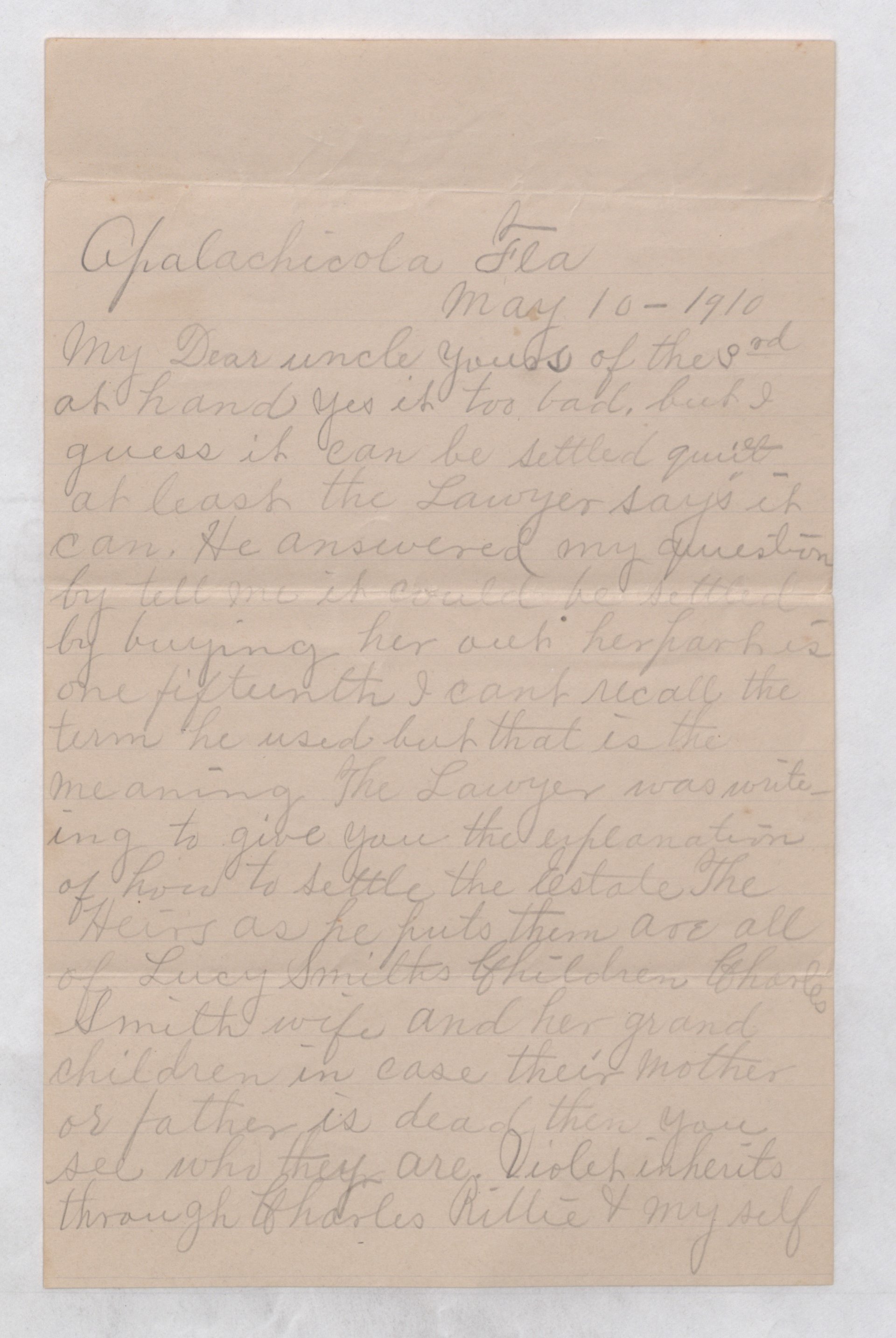

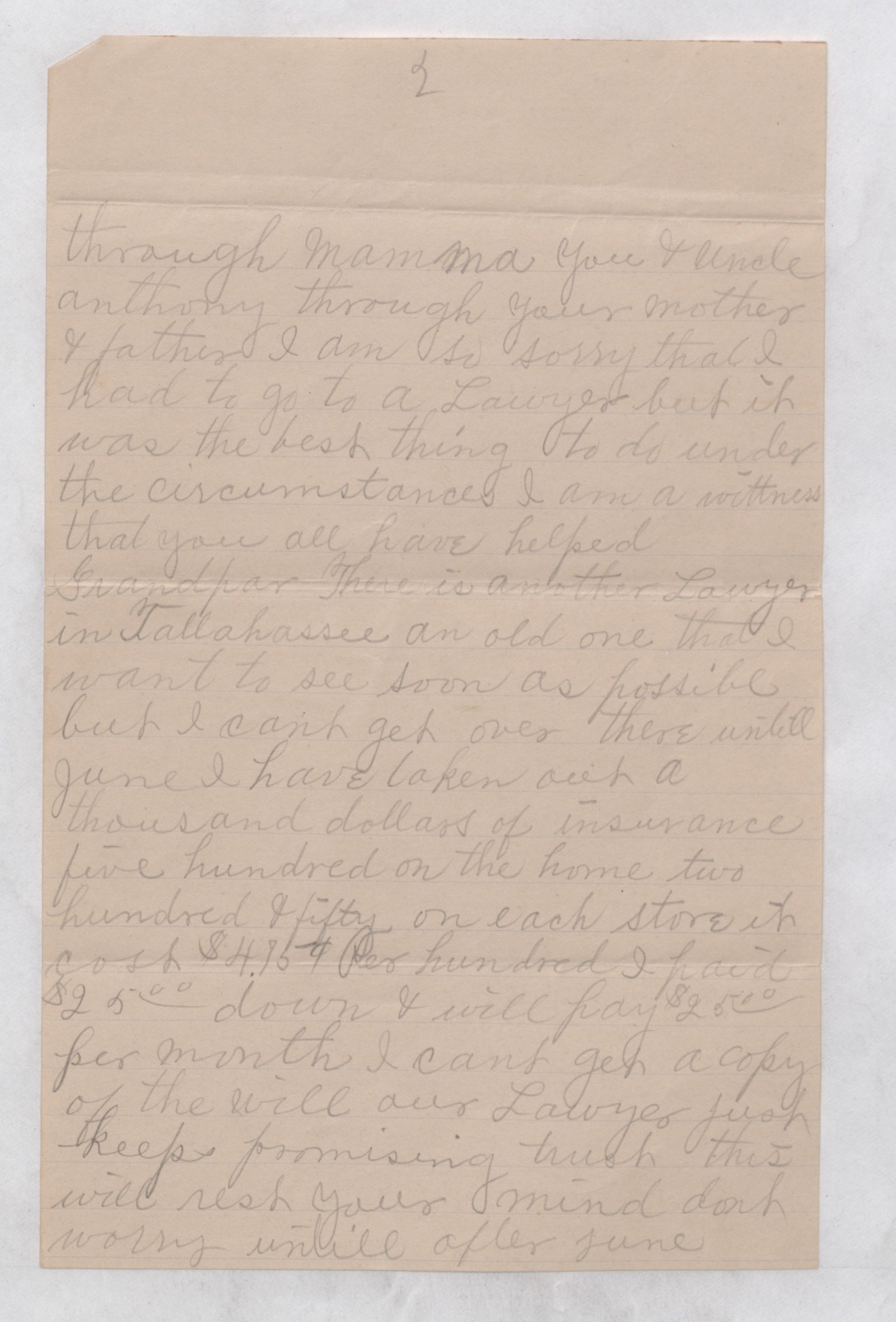

This letter, dated May 10, 1910, was written by Mary Hunter from Apalachicola, Florida, to her uncle Charles Smith Jr. in Savannah, and is preserved in the digital collections of the New York Public Library.

It shows how an African American family in the Jim Crow South acquired and maintained wealth, navigating the legal system to secure their property if necessary. Jim Crow refers to the formal and informal system of laws, customs, and behavior that enforced racial segregation and inequality across the South, severely limiting Black people’s ability to gain, hold, and transmit property—homeownership was often precarious due to discriminatory statutes, exclusion from credit, intimidation, and a biased legal system. In preserving their real estate property through legal means and insurance, the Smith family exercised remarkable agency within a racially discriminatory legal, economic, and social framework.

The letter was written in the aftermath of a family death, likely that of Charles Smith Sr., Mary’s grandfather. The estate appears to have included a house and at least two stores in Apalachicola. Mary writes about a legal dispute involving a female family member who wanted her share of the inheritance paid out in cash rather than jointly managing the properties. To resolve the matter, Mary consulted a lawyer and explained to her uncle that one possible solution was to "buy her out". She details the lawyer’s division of inheritance shares going to various family members, highlighting how multiple generations of the family were recognized as heirs. Mary also mentions that she has taken out insurance on the family’s property, underlining her dedication to preserve the inherited wealth.

This letter reveals not just conflict but competence: Mary’s actions show a clear understanding of the legal tools available to her. Her choice to consult not only one, but two lawyers, insure the property, and advocate for shared ownership illustrates how Black families, even under oppressive conditions, made strategic use of the law to secure intergenerational wealth. Mary’s active involvement in negotiating and managing the family estate provided a measure of financial security to following generations of the family. Two of Charles Smith’s daughters, Lula and Melinda, together with their cousin Madeline, for example, purchased the family house in Savannah five years after the inheritance and continued to live in it until their deaths in the 1960s/1970s. Mary’s and their achievement becomes even more significant when placed in a broader historical and structural context: the transfer of inherited wealth has long been a key driver of economic inequality in the United States. To this day, White households hold six to ten times more wealth than Black households on average, vividly illustrating the racial wealth gap. Against this backdrop, the Smith family's ability to retain and reinvest their inheritance stands out as a striking example of resilience and strategic property formation.

This case is significant for the SFB Structural Change of Property and the subproject A02 on racial capitalism because it provides a different perspective on the dominant narrative that Black Americans in the early 20th century were systematically excluded from property ownership. While structural barriers were real and persistent, sources like this letter demonstrate how African American families found ways, legally and socially by pooling resources, to build, retain, and protect property.