von Varun Patil

Occupation of public land by urban poor for housing and livelihood has a long history in Modern twentieth century in Mumbai, the financial capital of India. Public land is a specific historical land category introduced by the colonial state to indicate land ownership of state. After independence from the British colonial rule in 1947, the local Municipal authorities, conditioned on modern planning logics of city governance, successfully carried out large scale evictions of urban poor neighbourhoods and resettlement on outskirts.

The governmentality politics shifted with the ascent of the populist Indira Gandhi headed government in the 1970’s who looked to urban poor to gain legitimacy and ward off internal party struggles. The housing policy of the poor shifted towards “in-situ” rehabilitation and granting legal recognition to the occupation. The introduction of the Decadal Slum Survey Census in 1976 instituted the photo pass as a legal document for recognition of the occupancy and contains the annual taxes paid to the municipality. However, these rights of use do not include comprehensive property rights.

One of the urban poor neighbourhoods which survived the evictions in Mumbai was Dharavi, popularly known as Asia’s largest slum and now home to nearly one million residents. It was largely created by lower caste migrants incrementally filling up the marshy land in the 1970’s and represents a hotspot of struggles for housing by the urban poor in India and the Global South in general. Dharavi is currently again in the center of attention due to the ongoing Dharavi Redevelopment Project which started in 2004 and represents one of the most ambitious large-scale projects of urban renewal of urban poor neighbourhoods. However, many residents in Dharavi may not possess photo passes or have not transferred the ones purchased from an earlier occupant in their name. Most new hut buyers or new inheritors have not bothered to initiate the photo pass transfer mechanism as they feel safe with the Decadal Slum Survey Census slip. Many residents also do not transfer the photo pass as they reason it will be a costly procedure, given the many layers of bureaucracy. Officially, the costs amount to 40-60.000 Indian rupees (400-630 euros now), indeed effectively summing up to 200.000 Indian rupees due to corruption (2.100 euros). In recent times, the municipality also issues a photo identity card to supplement the older photo pass which is interestingly given in the name of both the husband and wife and contains various details of the hut occupation.

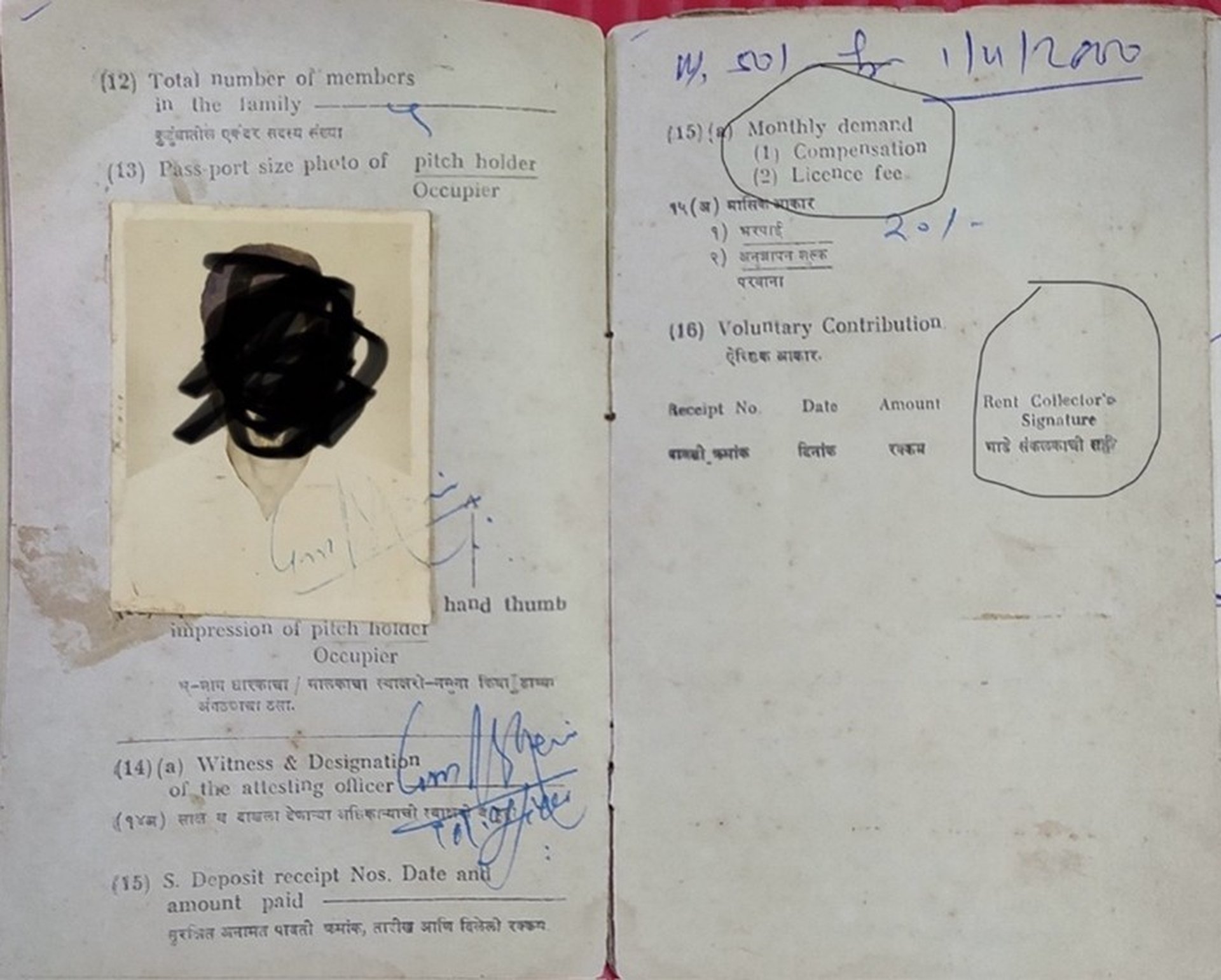

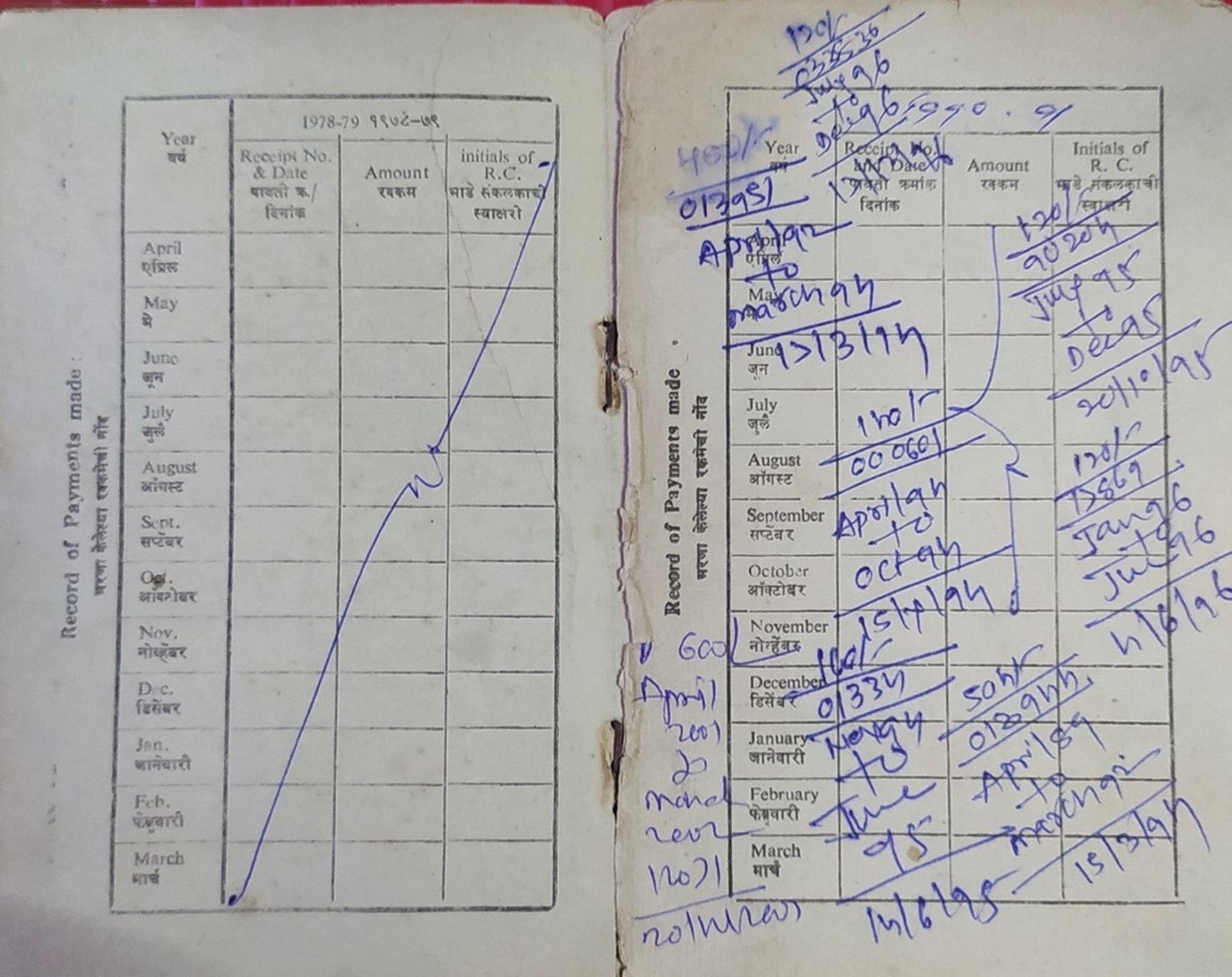

Presented below is a 1980’s period photo pass of a slum dweller. In Photo 1, we see the amount taken is classified as licence or compensation fee and not as rent, though the officer collecting the amount is tagged as a rent collector. In Photo 2, we see the tax taken for a hut in 1990 when this hut entered the municipality records. In photo 3, we see the various family members listed and the nature of relationship with the pass holder. In photo 4, we see the rules of the photo pass, including a ban on sub-letting and claiming property rights. Although since 2015 the state has allowed the transfer of photo pass to new hut owners, the limited set of rights and the lack of providing a land ownership title indicates the continued treatment of the urban poor as secondary class citizens. However, the legal-plural and competitive local democracy facilitates a bundle of rights expanding the limited rights given by the photo pass, a situation which can be termed as an ownership-right-in-practice.[1]. This points us to the importance of a sociological reading of property relations, one where effectiveness of any ownership situation does not flow automatically from any singular codified right but is a relational effect of the local socio-political dynamics.

[1] Patil, V./Fuchs, M. (2024): Ownership rights in practice: Property dynamics in an urban poor settlement in Mumbai – The exemplary case of Dharavi, in: Berliner Journal für Soziologie 34 (4), pp. 611–645, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11609-024-00543-2.